Masterpiece Conversations: Post-War Prints

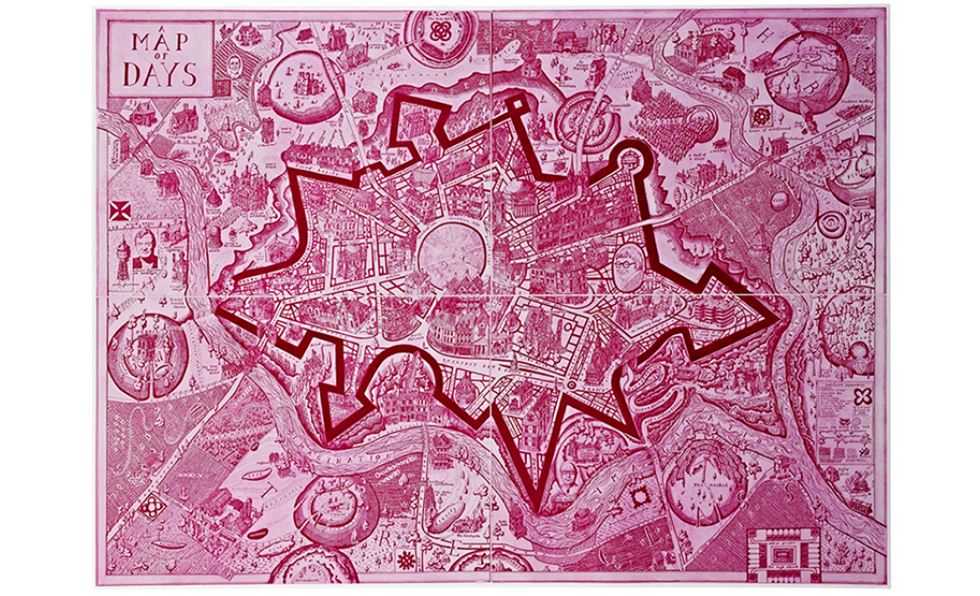

Image: Map of Days (Red), 2013 by Grayson Perry. Etching printed in colour, signed and numbered verso from the edition of 20, 111.5 x 151.5 cm. Courtesy of Lyndsey Ingram.

Masterpiece Conversations bring together leading young art dealers and curators to share their expertise. The first in this new series gives insights into collecting post-war prints with Lyndsey Ingram and Catherine Daunt.

Lyndsey Ingram is the founder of the eponymous gallery in Mayfair, London, which launched in 2016, specialising in modern and contemporary British and American prints.

Catherine Daunt is Hamish Parker Curator of Modern and Contemporary Graphic Art at the British Museum, London, where she was the project curator for ‘The American Dream: pop to the present’ in 2017.

How did you come to specialise in this field?

Lyndsey Ingram: When I applied for an internship in the books department at Sotheby’s London in 1999, they said, ‘We don’t take interns, but we’ve sent your CV to the HR team.’ HR asked me if I’d be happy to join the print department, and I said I’d love to – and from that moment I was hooked, basically. I was an intern for two summers there, then the department hired me when I graduated, and I later went on to work for a print gallery.

Catherine Daunt: I came into prints and drawings having previously worked in curatorial positions across media and periods at the National Portrait Gallery and Nottingham Castle. I gradually became more interested in works on paper, took some time out to do a PhD, then applied for a paid internship at the British Museum. That felt like a bit of a step backwards, because I’d already worked as an assistant curator – but I wanted to build up my knowledge of prints and drawings. In those six months I learnt so much from my colleagues in the department, and became completely convinced that I wanted to specialise. Seeing the range of the techniques, aesthetics and styles in the 20th-century and contemporary print holdings at the British Museum opened my mind to how diverse printmaking is. Since then, I’ve just learnt on the job, really.

Lyndsey Ingram: Some people have a sensitivity to paper; they just love it. And what’s almost always true with prints is that the images are very strong – they’re considered, they’re complete – because artists are aware that they’re making more than one of them.

The print world is sometimes pigeonholed as a field that only really interests connoisseurs. Do you recognise that characterisation?

Catherine Daunt: Different kinds of people are interested in prints – some who are obsessed with technique, others who find the details fascinating. But I do think that many people are a bit intimidated by the idea of looking at prints, because they feel like they don’t understand how they’re made. That can be quite a challenge for curators…

Lyndsey Ingram: Very knowledgeable colleagues in their fields – painting, sculpture or whatever – will sometimes come to screen-printing demonstrations at the gallery and say, ‘My God, I had no idea that that’s how they’re made.’ Prints require more than a pencil or a paintbrush – more than the most basic implements for making art – and the techniques can seem confusing or intimidating. And now that we live in a world with so much digital reproduction, they can seem even more confusing, because many people think that there’s some form of reproduction involved in printmaking, which just isn’t the case with most types of print.

Catherine Daunt: Outside the art world, a print can just mean…

Lyndsey Ingram: A poster. That’s the worst.

Catherine Daunt: Explaining technique is a real challenge for curators working with prints. We want people to understand how prints were made, so they’ll appreciate how much creativity and skill is involved. But that can be very dry: you can have a panel explaining all the different techniques, but they’re still difficult to visualise. What really helps is using video footage in exhibitions, and the fact that there are now so many videos online that show how prints are made. In ‘The American Dream: pop to the present’ we included a video of Andy Warhol screen printing.

Is it difficult to convince the public that, as multiples, prints are not somehow secondary to paintings?

Lyndsey Ingram: People accept photographs, and people accept sculpture, which is often cast in editions. And more and more artists are working in edition – it’s usually to their commercial advantage. I think that some people just stumble over the word ‘print’.

Catherine Daunt: I think it can be… I often get asked, about a print, ‘Is this an original?’ and what people mean by that is, ‘Is it unique?’ I think the problem is partly to do with the terminology, using words like ‘state’, which most people aren’t familiar with. Again, a video can help with that, or showing actual plates and other objects relating to the process of printmaking.

What challenges do post-war prints pose for display and conservation?

Lyndsey Ingram: For me, it’s important that we frame everything to the highest standard currently available in the market. So everything is framed with acid-free mount board and UV-filtering Plexiglas. I’d be doing my clients a huge disservice if I sent anything out of the gallery that wasn’t in the best product possible. And we believe in that product, we believe that it protects things from acid or fading – but you regularly open prints that were framed 20 or 30 years ago and were sent in the world with the same understanding, and which are now faded or mount-stained. I know we do the best we can.

Catherine Daunt: From our point of view at the museum, exposure is the main challenge. We do want to display the prints and we do want to lend them, but we know that they will fade over time with too much exposure. That’s particularly true of works where unusual, perhaps unpredictable, materials have been used, which often applies to post-war prints: we have a set of screen prints by Ed Ruscha, for example, which are printed with organic materials like bits of food – baked beans and chocolate sauce – and we have to monitor those very carefully, because even if they seem fairly stable, we don’t really know what’s going to happen. The other major problem that we have is storage. Ideally, everything would be framed, but we don’t have the capacity to do that, so we have to make sure that things are looked after the best way they can be.

How dynamic is this field at the moment?

Lyndsey Ingram: It’s definitely a dynamic place in terms of where prints sit in the marketplace. When I started 20 years ago, it was a very closed world, and prints by major artists were often cordoned off from their other work. But how could you look at a Warhol Marilyn canvas without comparing it to his Marilyn screen prints? About a decade ago, things changed: important prints started showing up in contemporary evening sales, and then all of a sudden, big galleries are showing prints in very high-profile ways, like at major art fairs. It’s great that prints are now being seen in the context of other work by the same artist. It definitely means the way that we work has to change, but I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

Catherine Daunt: I agree. It’s definitely a good thing to see more prints at art fairs and in sales, but I do think that there’s still a resistance among some public institutions and curators to include prints in retrospective exhibitions. With artists for whom printmaking has been a major part of their work, exhibitions will often only display a very small number of prints, and usually in an illustrative way that prioritises other media. For those artists, printmaking wasn’t just something they did to reproduce images or to sell works to people who couldn’t afford their paintings, it was a really important part of their activity. It’s also important they were collaborating with other people, spending time in print workshops. Collaboration and the input of master printers are areas of printmaking that aren’t really discussed enough by academics and curators.

Lyndsey Ingram: A good printer helps an artist realise something that they didn’t know they could realise. It’s a process of artists being taught more about how they can express their ideas. With painting, that process often ends when an artist leaves art school. But if you watch what happens between a very established artist and a printer they’ve never worked with before… it’s real magic.

Catherine Daunt: I’ve recently been researching some Howard Hodgkin prints. Whenever he began to work with a different printer, his printmaking really developed: when he started working with Maurice Payne, for example, he was introduced to sugar lift aquatint, and he started using hand-colouring and soft-ground etching. Collaborating with a master printer enabled him to make work that he wouldn’t otherwise have been able to make.

How difficult is it for museums to make acquisitions in this field?

Catherine Daunt: With certain contemporary prints it can be. With American prints, the prices are rising and we’re obviously constrained by budgets, so we rely increasingly on private philanthropy through patrons, and also on gifts and bequests.

Lyndsey Ingram: It’s really important that museums have major collections of post-war prints. I can’t speak for everyone, but I feel a responsibility as a member of the trade to help museums acquire as much as they can as affordably as possible. We always encourage our artists to give things to the British Museum. If you’re making an edition, make one more and call it the BM proof. It costs so little, and in time, it means so much.

Has the collector base changed in the past decade?

Lyndsey Ingram: For sure. Everything is more expensive than it used to be, particularly for prints made by blue-chip artists. Owning a nice Hockney print is a much more substantial commitment now than it would have been 10 or 15 years ago. Higher up the scale, more people are coming to the better prints by more established artists because they can’t afford a painting. If you want a major and meaningful work by Lichtenstein, who was an amazing printmaker, you can buy an important print for $100,000 or $200,000. The paintings now cost more than almost anyone can afford.

Could museums and the art trade collaborate more effectively in this field?

Catherine Daunt: One of the most important things is to ensure that our collections are accessible: at the British Museum, we’ve had to reduce the opening hours of our study room, but it’s still open from Tuesday to Friday. At some institutions, you need to make appointments to see graphic works in storage six weeks, even two months in advance. If you’re a dealer or just someone interested in doing some research on a print, you often have to react more quickly than that. It’s vitally important that people can come and use our collection and study it.

Lyndsey Ingram: I appreciate that there are boundaries: it becomes problematic when museums get a reputation for putting on shows that, say, benefit the collections of the board of trustees. That said, I think there are a lot of things that could change with a bit of imagination, to the mutual benefit of commercial and public galleries. Perhaps this is more true of prints than other fields – but we just like what we do, we’ve chosen to do it, and we all know each other.

Catherine Daunt: That’s what I mean. We don’t need to make sure our collections are accessible to dealers for the sake of their sales; dealers are doing research in the same areas that we are, and they might want to come and compare different impressions or different states of a print. We can all help each other to learn more about the work that we’re looking at.